- emedicine.medscape.com - Peptic Ulcer Disease

- webmd.com - What Is a Peptic Ulcer?

- gi.org - Peptic Ulcer Disease

- medlineplus.gov - Peptic Ulcer

- healthline.com - Stomach Ulcer Diet

- webmd.com - Best and Worst Foods for Stomach Ulcers

Peptic ulcer disease: Causes, Symptoms

A peptic, or gastric (stomach), ulcer is an open wound of the inner lining of the stomach. Pain is one of the symptoms. Why does it develop?

Characteristics

Pain in the upper abdomen is the most common symptom of both gastric and duodenal ulcers, characterised by a biting or burning sensation, and occurs after eating - classically shortly after eating for gastric ulcers and 2-3 hours afterwards for duodenal ulcers.

Gastroduodenal ulcers, gastroduodenal ulcer disease, peptic ulcer, gastric and duodenal ulcer/ulcer disease of the stomach and duodenum.

Anatomy and physiology of the stomach

The stomach is a sac-like organ in the upper part of the digestive tract between the oesophagus and the small intestine. It provides a number of important functions necessary for the beginning of the digestive process.

The motor activity of the stomach depends on its function. It serves as an accumulation organ for food, ensures the mixing and mixing of food with gastric juice, and regulates the amount of food it releases into the small intestine.

Stomach acid initiates digestion by denaturing ingested food and promoting enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins. In addition to these digestive functions, due to the highly acidic nature of gastric juice, the stomach also provides for the reduction of ingested microorganisms.

In addition, a component of gastric juice called intrinsic factor promotes the absorption of vitamin B12, which is important for the normal maturation of red blood cells.

Definition and formation of ulcers

Peptic ulcers are defects in the lining of the stomach or duodenum that pass through the muscular layer of the stomach. They arise when the protective mucus that lines the stomach becomes ineffective.

The stomach produces a strong acid - hydrochloric acid, which helps in the digestion of food and protects against microbes. It also secretes a thick layer of mucus to protect the body's tissues from this acid.

If the mucus layer is insufficient and stops working effectively, the acid can damage the tissue of the stomach and cause an ulcer.

Causes

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- drug abuse

- lifestyle factors

- severe physiological stress

- hypersecretory states (uncommon)

- genetic factors

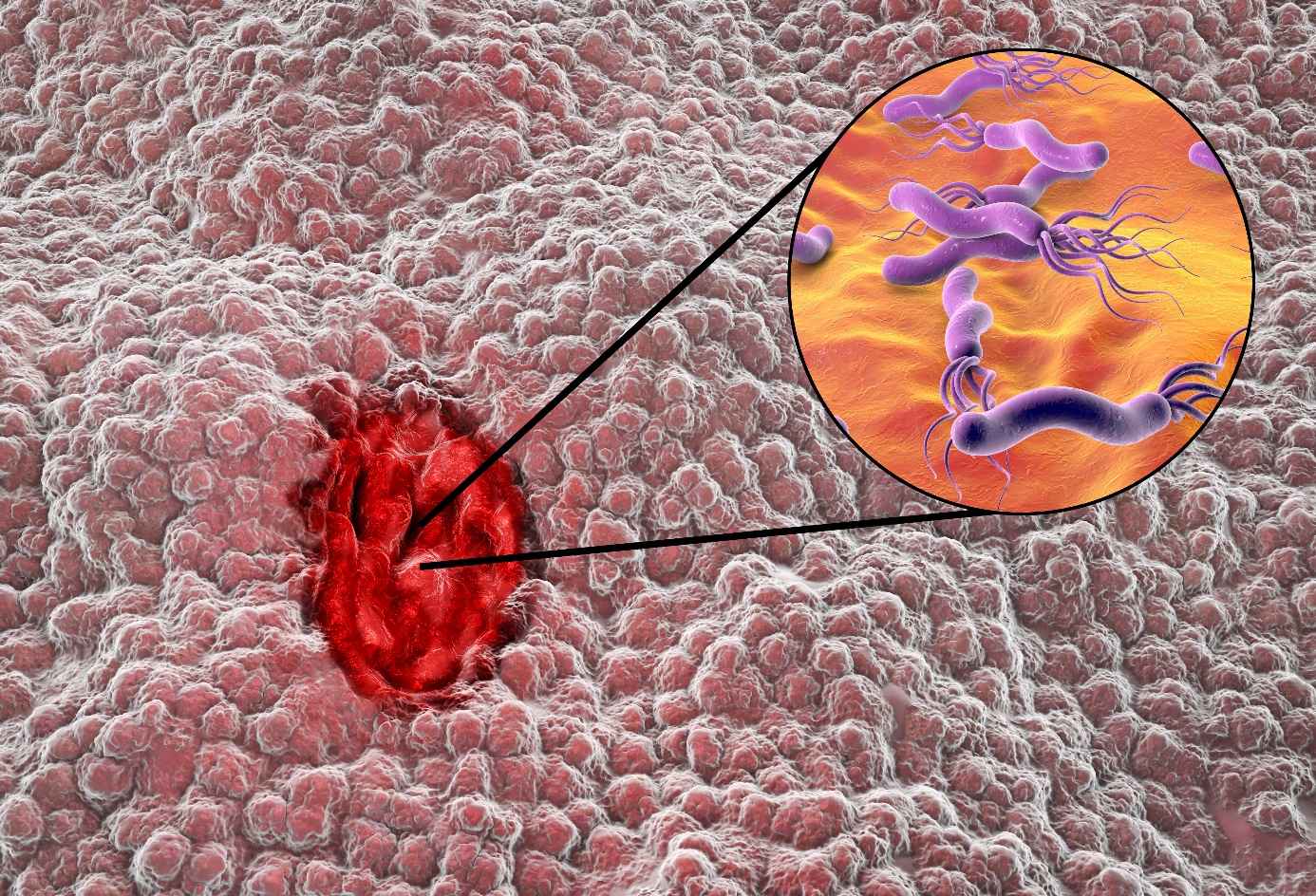

Infekcia Helicobacter pylori

H. pylori infection and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) account for the majority of cases of peptic ulcer disease.

The prevalence of H pylori infection in complicated ulcers (i.e., bleeding, perforation) is significantly lower than in uncomplicated ulcer disease.

Medicines

The use of NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs - acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen, flurbiprofen, ketoprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, indomethacin, coxanes) is a common cause of peptic ulcer disease.

These drugs disrupt the mucosal permeability barrier, making the mucosa vulnerable to injury. Up to 30% of adults taking NSAIDs experience adverse effects in the gastrointestinal tract.

Factors associated with an increased risk of ulceration with NSAID use include a history of previous peptic ulcer disease, older age, female sex, high doses or combinations of NSAIDs, long-term use of NSAIDs, concomitant use of anticoagulants, and significant comorbid diseases.

A long-term prospective study found that arthritis patients who were over 65 years of age and who regularly took low-dose aspirin had an increased risk of dyspepsia (indigestion) severe enough to require discontinuation of NSAIDs.

This is why the use of NSAIDs in elderly patients should be cautious.

A retrospective study in the United Kingdom of patients started on low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events (after myocardial infarction) identified risk factors for uncomplicated ulcer disease in these patients, which included the following:

- previous history of peptic ulcer disease.

- concomitant use of NSAIDs, oral steroid medications, or acid-suppressing drugs.

- tobacco use

- stress

- depression

- anemia

- social deprivation

Although this idea was initially controversial, the majority of evidence supports the claim that H. pylori and NSAIDs are synergistic with respect to the development of peptic ulcer disease.

A meta-analysis found that eradication of H. pylori in users with no prior NSAID treatment before starting NSAID therapy was associated with a decrease in peptic ulcers.

Although the prevalence of NSAID gastropathy in children is unknown, it appears to be increasing, especially in children with chronic arthritis treated with NSAIDs. Case reports have demonstrated gastric ulceration from low-dose ibuprofen in children, even after as little as 1 or 2 doses.

Corticosteroids alone do not increase the risk of peptic ulcer disease; however, they may increase the risk of developing ulcers in patients who are concomitantly taking NSAIDs.

The risk of upper GI tract bleeding may be increased in users of diuretic spironolactone or antidepressant serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Lifestyle factors

The evidence that tobacco use is a risk factor for duodenal ulcers is not conclusive. Support for a pathogenic role for smoking comes from the finding that smoking may accelerate gastric emptying and reduce bicarbonate production in the pancreas.

However, studies have produced conflicting findings. In one prospective study of more than 47,000 men with duodenal ulcers, smoking was not shown to be a risk factor.

However, smoking during H. pylori infection may increase the risk of recurrence (reoccurrence) of peptic ulcer disease. Smoking is harmful to the gastroduodenal mucosa, and H. pylori infiltration is more numerous in the stomach of smokers.

Ethanol is known to cause irritation of the gastric mucosa and non-specific gastritis. Evidence that alcohol consumption is a risk factor for peptic ulcers is also inconclusive.

A prospective study of more than 47 000 men with duodenal ulcers found no association between alcohol intake and duodenal ulcers.

Little evidence suggests that caffeine intake is associated with an increased risk of peptic ulcers.

Severe physiological stress

Stressful conditions that can cause peptic ulcer disease include burns, central nervous system (CNS) trauma, surgery, and serious medical illnesses.

Severe systemic disease, sepsis, hypotension, respiratory failure and multiple traumatic injuries increase the risk of secondary (stress) ulceration.

Cushing ulcers are associated with a brain tumor or trauma and are usually single deep ulcers that are prone to perforation. They are associated with high gastric acid output and are located in the duodenum or stomach.

Extensive burns are associated with Curling's ulcers.

Stress ulcers and upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding are complications that are increasingly encountered in critically ill children in the intensive care setting.

Severe illness and reduced gastric pH are associated with an increased risk of gastric ulcers and bleeding.

Hypersecretory states (less common)

The following conditions are among the hypersecretory conditions that can, less commonly, cause gastric ulcer disease:

- gastrinoma (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome) or multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN-I).

- hyperplasia of antral G cells.

- systemic mastocytosis.

- basophilic leukemia.

- cystic fibrosis.

- short bowel syndrome.

- hyperparathyroidism.

Genetics

More than 20% of patients have a family history of ulcers compared to only 5-10% in controls. In addition, weak associations between duodenal ulcers and blood group 0 were observed.

In addition, patients who do not secrete AB0 antigens in saliva and gastric juices are known to be at higher risk. The reason for these apparent genetic associations is unclear.

There is a rare genetic link between familial type I hyperpepsinogenemia (a genetic phenotype leading to increased pepsin secretion) and duodenal ulcers.

However, H. pylori can increase pepsin secretion, and a retrospective analysis of the serum of one family studied before the discovery of H. pylori revealed that their high pepsin levels were more likely to be associated with H. pylori infection.

Other etiological factors

Peptic ulcer disease can be associated with any of the following:

- cirrhosis of the liver

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- allergic gastritis and eosinophilic gastritis

- cytomegalovirus infection

- graft-versus-host disease

- uremic gastropathy

- Henoch-Schonlein gastritis

- corrosive gastropathy

- celiac disease

- bile reflux gastropathy

- autoimmune diseases

- Crohn's disease

- other granulomatous gastritis (e.g. sarcoidosis, histiocytosis X, tuberculosis).

- phlegmonous gastritis and emphysematous gastritis.

- other infections including Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, Helicobacter heilmannii, herpes simplex, influenza, syphilis, Candida albicans and histoplasmosis.

- chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), methotrexate (MTX) and cyclophosphamide.

- local irradiation, which leads to mucosal damage that can lead to the development of duodenal ulcers.

- cocaine use, which causes localised vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels), leading to reduced blood flow and can lead to mucosal damage.

Symptoms

Medical history

To establish a correct diagnosis, it is essential to obtain a medical history, in case of H. pylori infection, ingestion of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or smoking.

Gastric and duodenal ulcers cannot usually be distinguished on the basis of history alone, although some findings may suggest one or the other.

Pain in the upper abdomen is the most common symptom of both stomach and duodenal ulcers. It is characterised by a burning sensation and occurs after eating - classically shortly after a meal with a gastric ulcer and 2-3 hours afterwards with a duodenal ulcer.

Food or antacids relieve the pain of duodenal ulcers but provide minimal relief from the pain of gastric ulcers.

Unlike a stomach ulcer, the pain of a duodenal ulcer often wakes the patient up at night. About 50-80% of patients with duodenal ulcers experience nocturnal pain, as opposed to only 30-40% of patients with gastric ulcers.

Pain usually follows a daily pattern specific to the patient. Pain with radiating to the back suggests a penetrating gastric ulcer at the back of the stomach, complicated by pancreatitis.

Patients who develop obstruction (closure) of the gastric outlet due to chronic, untreated gastric or duodenal ulcer usually give a history of fullness and bloating associated with nausea and vomiting occurring several hours after food intake.

A common misconception is that adults with gastric outlet obstruction have nausea and vomiting immediately after eating.

Other possible manifestations include:

- dyspepsia (indigestion), including burping, bloating and intolerance to fatty foods.

- heartburn

- chest discomfort

- haematemesis (vomiting of blood) or melena (black feces) due to gastrointestinal bleeding. Melena may be intermittent over several days or may have multiple episodes in one day.

- rarely, a rapidly bleeding ulcer may manifest as rectal bleeding.

- symptoms consistent with anaemia (e.g. fatigue, shortness of breath) may be present.

- sudden onset of symptoms (especially pain) may indicate perforation (perforation) of the stomach.

- gastritis (inflammation of the stomach) or ulcers caused by anti-inflammatory drugs and painkillers may be asymptomatic, especially in elderly patients.

Alarming symptoms that require an immediate referral for examination by a gastroenterologist include the following:

- bleeding or anaemia

- early satiety

- unexplained weight loss

- progressive dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) or odynophagia (painful swallowing)

- recurrent vomiting

- family history of digestive tract cancer

Conditions that can mimic a stomach ulcer:

- acute cholangitis (inflammation of the bile ducts)

- acute gallbladder inflammation and biliary colic

- acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction)

- acute or chronic gastritis

- diverticulitis

- oesophagitis (inflammation of the oesophagus)

- gallstones

- gastroesophageal reflux disease

- inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease)

Diagnostics

Testing for Helicobacter pylori

Testing for H. pylori infection is essential in all patients with peptic ulcers.

Endoscopic or invasive tests for H. pylori include a rapid urease test, histopathology, and culture. Rapid urease tests are considered the endoscopic diagnostic test of choice.

The presence of H. pylori in gastric mucosal biopsy specimens is detected by testing for the bacterial product urease. Fecal antigen testing identifies active H. pylori infection by detecting the presence of H. pylori antigens in stool.

This test is more accurate than antibody testing and is cheaper than urea breath tests.

If the rapid urease test is negative and a high suspicion of H. pylori persists (presence of duodenal or gastric ulcer), histopathology should be obtained by taking a sample from the stomach, which is often considered the standard criterion for the diagnosis of H pylori infection.

Antibodies (immunoglobulin G - IgG) against H. pylori can be measured in serum, plasma or whole blood. However, the test is not suitable for the diagnosis of active infection, as antibodies remain positive for a long time after infection.

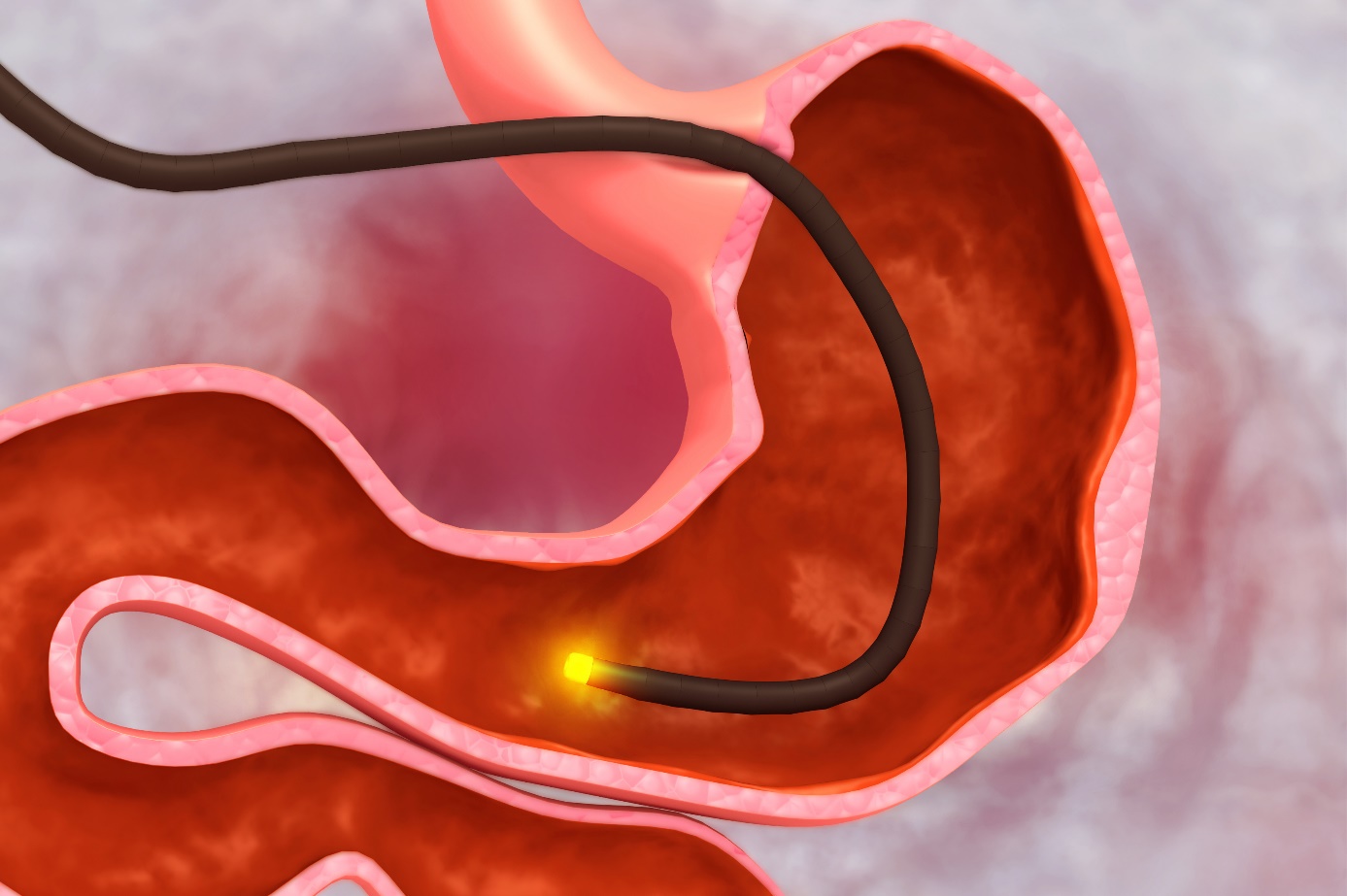

Endoscopy

Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract is the preferred diagnostic method for diagnosing patients with suspected peptic ulcer disease.

It is highly sensitive for the diagnosis of gastric and duodenal ulcers, allows biopsy and cytological examination in the setting of a gastric ulcer to differentiate a benign ulcer from a malignant lesion, and allows detection of H. pylori infection by biopsy.

On endoscopy, gastric ulcers appear as separate mucosal lesions with a raised smooth base of the ulcer, which is often filled with whitish fibrinoid exudate. The ulcers tend to be solitary and well demarcated and are usually 0.5-2.5 cm in diameter.

Benign ulcers tend to have a smooth, regular, rounded margin with a flat smooth base and surrounding mucosa.

The dreaded malignant ulcers usually have irregular accumulated or overhanging margins. The ulcerated mass often protrudes above the surface of the other mucosa, and the folds surrounding the ulcer crater are often nodular and irregular.

Radiographic methods

In patients with an acute presentation, a chest X-ray to detect free air in the abdominal cavity may be useful when perforation (perforation) is suspected.

Double-contrast radiography performed by an experienced radiologist can approach the diagnostic accuracy of upper gastrointestinal (GIT) endoscopy. However, it has been largely superseded by diagnostic endoscopy when available.

Radiography of the upper GIT is not as sensitive as endoscopy for the diagnosis of small ulcers (< 0.5 cm).

It also does not allow obtaining a biopsy to rule out malignancy in the setting of a gastric ulcer or to assess for H. pylori infection in the setting of a gastroduodenal ulcer.

Angiography

Angiography may be necessary in patients with massive gastrointestinal bleeding in whom endoscopy cannot be performed.

For angiography to be able to accurately identify the source of bleeding, a bleeding rate of 0.5 ml/min or more is required.

Angiography can show the source of the bleeding and can help provide the necessary therapy in the form of direct injection of vasoconstrictors.

Serum gastrin level

When Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is suspected, a serum gastrin level should be obtained on an empty stomach in certain cases. Such cases include:

- patients with multiple ulcers

- ulcers occurring lower in the duodenum

- strong family history of peptic ulcer disease

- peptic ulcer associated with diarrhoea, steatorrhoea or weight loss

- peptic ulcer unrelated to H pylori infection or to the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- peptic ulcer associated with hypercalcaemia (raised blood calcium levels) or kidney stones

- ulcer resistant to treatment

- recurrent ulcer after surgery

Biopsy and histological findings

Biopsy

A single biopsy offers 70% accuracy in the diagnosis of gastric cancer, but 7 biopsy specimens obtained from the margins of the base and ulcer increase the sensitivity to 99%.

Brush cytology has been shown to increase biopsy yield, and this method may be particularly useful when bleeding at biopsy collection is a problem in a patient with a bleeding condition.

Histological findings

The histology of gastric ulcer depends on its duration. The surface is covered with putrefaction and inflammatory changes. Beneath this inflammatory infiltration, active inflammation with white blood cells and dead tissues can be seen.

When assessing ulcer specimens, the most important finding is the presence of malignant cells that might be present in the ulcer.

Diet tips for gastritis and stomach ulcers

Doctors often advise people with ulcers to change their lifestyle and diet, in addition to medication, until there is a complete cure.

Although in the past patients have been encouraged to follow a bland diet, current research does not support this diet modification as beneficial.

Although spicy foods are irritating to some people with ulcers, doctors are now placing more emphasis on a diet high in fiber, rich in vegetables and fruits.

Current dietary recommendations are now based on research that some foods may contain ingredients that fight the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which is a major cause of ulcers.

fibre and vitamin A

Research shows that a high-fibre diet reduces the risk of developing ulcer disease. Both insoluble and soluble fiber demonstrate this association, there is a stronger association between a diet high in soluble fiber and a reduced risk of ulcers.

Foods high in soluble fibre include oats, psyllium, legumes, flaxseeds, barley, nuts and some vegetables and fruits such as oranges, apples and carrots.

Findings from the study, which included 47,806 men, showed that diets rich in vitamin A from all sources can reduce the development of ulcers, as can diets high in fruits and vegetables, presumably because of their fibre content.

Animal studies show that vitamin A increases mucus production in the gastrointestinal tract. Impaired mucosal defense may allow ulcers to develop. Therefore, vitamin A may have a protective effect against the development of ulcer disease.

Good sources of vitamin A include liver, carrots, broccoli, sweet potatoes, kale, spinach, and cruciferous vegetables.

green tea and foods rich in flavonoids

New research from China shows the potential protective effects of green tea and other flavonoid-rich foods against chronic gastritis, H. pylori infection and stomach cancer. Specifically, these foods appear to slow the growth of H. pylori.

In addition, one recent laboratory study of green, white, oolong and black teas showed that these teas slowed the growth of H. pylori but did not harm beneficial types of bacteria commonly found in the stomach, including L. acidophilus, L. plantarum and B. lungum.

However, this was an in vitro study, which means that the testing was directly between the teas and the bacteria in the laboratory, and we cannot draw direct conclusions about what would happen between the two substances in the human body.

The beneficial effects in the laboratory were best when the tea was infused for a full five minutes.

Foods rich in flavonoids include garlic, onions, and colorful fruits and vegetables such as cranberries, strawberries, blueberries, broccoli, carrots, and peas.

coffee and alcohol

Both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee can increase acid production and worsen symptoms in individuals with ulcer disease. Alcoholic beverages can disrupt the protective lining along the gastrointestinal tract and lead to further inflammation and bleeding.

To minimize symptoms, individuals with ulcer disease should avoid or limit both coffee and alcohol.

cranberry juice

Drinking just two 250 ml cups of cranberry juice cocktail a day can reduce the risk of H. pylori overgrowth in the stomach. Concerns about antibiotic resistance make this finding particularly significant because cranberry tannins appear to block the bacteria without killing them.

When antibiotics are used to kill the infection, the bacteria can mutate and become resistant to treatment. Cranberry helps by either not allowing the bacteria to take hold, or by repelling them from the body once they attach, and preventing inflammation.

So drink up, cranberry juice is good for you!

Individual food tolerance is important

No evidence suggests that spicy or citrus foods affect ulcer disease, although some individuals report worsening of symptoms after eating these types of foods.

It is important to find out what works for you.

If you notice that your symptoms worsen after eating certain foods, limit or avoid them to feel your best and make sure you don't rule out an entire food group.

In short, if you suffer from peptic ulcer disease, then focus on a diet high in fiber and rich in vegetables, fruits and whole grains.

Try to eat at least seven portions of vegetables and fruit and at least five portions of whole grains every day. Choose foods that are good sources of soluble fibre, vitamin A and flavonoids.

Consider adding tea to your daily beverage list. If you drink alcohol, do so in moderation, with a maximum of two drinks per day and a maximum of nine drinks per week for women (fourteen for men).

Can peptic ulcers be prevented?

Peptic ulcers can be prevented by avoiding drugs and habits that disrupt the protective barrier of the stomach and increase gastric acid secretion. These include alcohol, smoking, aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and caffeine.

Prevention of H. pylori infection involves avoiding contaminated food and water and following strict personal hygiene rules. Wash your hands thoroughly with warm water and soap every time you use the bathroom, change a diaper, and before and after preparing food.

If you need the pain relief and anti-inflammatory effect of aspirin or NSAIDs, you can reduce your risk of ulcers by trying the following:

- try other medicines, ones that are easier on the stomach (e.g. paracetamol).

- reduce the dose or number of repetitions of taking the medicine.

- Talk to your doctor about how you can protect yourself.

Following your treating doctor's treatment recommendations can help prevent ulcers from recurring. This includes taking all medications as prescribed, especially if you have an H pylori infection.

How it is treated: Peptic ulcer disease

What is the treatment for peptic ulcers? Medicines for stomach ulcers and surgery.

Show morePeptic ulcer disease is treated by

Other names

Interesting resources