Conjunctival disorders

Conjunctival disorders include

Conjunctival diseases mainly affect the conjunctiva itself, which is a thin, moist and blood-soaked mucous membrane located on the surface of the eye and on the inside of the eyelids, but in many cases, inflammatory diseases can be related to either the eyelid or the cornea, as these are the parts of the eye with which the conjunctival mucosa comes into direct contact. The conjunctiva is one of the appendages of the eye, passing into the corner of the eye on one side and into the cornea on the other.

Diseases of the conjunctiva mostly affect only the surface of the conjunctiva, but it is also possible to have vascular or degenerative diseases associated with the conjunctiva, which can interfere with the main functions of the conjunctiva, in particular its defensive functions against the cornea, the corners of the eye and the tear ducts, as well as against the eyelids. The most typical conjunctival problem is redness, which is also present in some chlamydial, herpetic, viral or adenoviral infections and inflammations, for example.

Structure of the conjunctiva

The conjunctiva is a mucous membrane that lines the space between the eyelids, the eyeball, and the eye socket and covers the underside of both the upper and lower eyelids, overlaps the visible portion of the white of the eye, and ends at the cornea. In addition to the eyelids, the conjunctiva is part of the eye's protective barrier against mechanical and chemical irritations and also prevents foreign bodies or germs and infections from entering the eye space from the external and exterior.

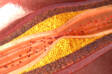

The conjunctiva as such is a thin and well vascularised moist mucous membrane of pale pink colour and is continuously connected to the corneal epithelium on the anterior side of the eye. It connects the eyeball to the eyelid and is nourished by very thin blood vessels, which, however, in a defensive reaction can intensely and very quickly enlarge and dilate, causing reddening of the conjunctiva. The conjunctiva has four parts. There is a space between the eye and the eyelid which is covered by the conjunctiva and is called the conjunctival sac. This narrow slit sac contains tears and tears flow here from the outlets of the lacrimal glands.

In addition to this, the coupling has three other parts. The part covering the inner side of the eyelid is called the lid conjunctiva and it is the peripheral epithelial zone where the cup-shaped mucous cells are also found. However, the margin of this part is smooth. The place where the conjunctiva passes from the eyeball to the inside of the eyelid is the part called the transitional lash. The upper transitional eyelash is located between the eyelid conjunctiva and the bulbar conjunctiva, the lower transitional eyelash allows movement of the eyelid and ends in the inner corner.

The bulbar part of the conjunctiva passes through the eyeball and the white of the eye, covering them and protecting them from both mechanical and infectious factors from the external environment. This part of the conjunctiva connects continuously to the corneal epithelium at its edge and continues through the visible part of the anterior eye directly into the arched space between the eye and the eyelid. As such, the conjunctiva is a relatively thin membrane, but very elastic and strong, which has several functions, including a protective one.

Functions of the conjunctiva

The role of the conjunctiva is to line the space between the eyelid, the eyeball and the eye socket, which is why this deep pink-coloured membrane adheres to the cornea, the tear ducts and the upper and lower eyelids. Due to the smooth movements of the eyeball, the conjunctiva is also important in terms of elasticity, but it also has mechanical and protective functions as well. It is the seat of immune cells, so any infections either on the mucous membrane or near the eye trigger an inflammatory counter-reaction in the conjunctiva by the immune system.

When irritated, the blood vessels with which this membrane is numerously interwoven dilate, and the blood vessels rapidly dilate and the conjuctivae, which are congested, become red. As part of its protective function, the conjunctiva is richly innervated, so that any irritation, infectious or mechanical, is reliably intercepted, which is manifested by its inflammation, pain, burning and cutting sensation. The conjunctiva also contains mucous cup-shaped cells that are near the lid margin and produce mucin, which is discharged onto the surface of the conjunctiva.

In this context, the secretory function of the conjunctiva is also very important, as the conjunctival epithelium contains various types of cells that also produce mucus and other important components of the tear film. These cells are also called Henle's crypts, and together in the upper and lower part with the accessory Krause's and Wolfring's glands, they participate in the moistening of the entire conjunctiva and also of its surrounding tissues and structures. In addition to moisturizing, they also protect the tissues from mechanical impurities.

With disorders of emptying of these glands, drying of the conjunctiva occurs, which is a symptom both for the pathological condition itself, but it can also be provoked by various asymptotic disease causes, so that the conjunctiva in this way gives an indication of a problem affecting the tissues close directly to the eye. The most important role of the conjunctiva, however, is to cover the visible outer part of the white of the eye, thus protecting the white of the eye from inflammation and other external non-infectious environmental influences.

Conjunctival inflammations

Most often, conjunctivitis affects the conjunctiva in various forms. Conjunctivitis, as these inflammations are technically called, can be of different types, namely mucopurulent, acute atopic, chronic conjunctivitis or blepharoconjunctivitis. Most often the inflammation is infectious, caused either by bacteria or viruses, but it can also arise on a non-infectious deposit, for example, when the mucous membrane is intensely irritated by chemicals, harsh light, or mechanical damage.

The most common are bacterial and viral conjunctivitis, which can have both an acute and chronic course. Adenoviruses among viruses, and possibly also viruses of other infections, are the most provocative of conjunctivitis. In bacterial infections of the primary type, inflammation caused by staphylococci and streptococci is most common. Depending on the speed and course of the disease, the inflammation can be hyperacute, when it occurs in a few hours, acute, which is a matter of a few days, and chronic, which lasts more than a month.

For bacterial inflammations, it is true that they are most common in winter and spring, and very often there is also a purulent form of inflammation. Thus, there is swelling of the eyelids, swollen nodes, redness and thick secretion. In viral inflammations, pain and itching of the eyes and watery eyes are typical symptoms. These infectious inflammations are relatively easy to spread, and thus, for example, poor hygiene or the use of shared towels can lead to transmission. Topical treatment is the most common treatment, and in chronic inflammation, total treatment is also used.

However, conjunctivitis can not only be triggered directly by infections or causes on the mucous membrane and near the eye, but often there is also transmission of infection from other parts of the body. This is true, for example, in viral infections with herpes viruses, chicken pox viruses, rubella viruses, and the like, when there is a passage of the infection through the bloodstream to the conjunctiva. Similarly, chlamydial infections or gonorrhoea can also manifest themselves by inflaming the conjunctivae.

Allergies, degenerations, ulcers and vascular problems

The conjunctiva is also affected by other diseases besides inflammation, such as various types of allergies, conjunctival degenerations and deposits such as conjunctival argiosis, adhesions, pigmentation or xerosis, as well as vascular diseases of the conjunctiva such as aneurysm, hyperemia or edema. Also, as a result of inflammation, ulcers can form on the conjunctiva, sometimes entering here by passage from the eyelids and spreading the ulcer infection.

Conjunctival allergies affect, for example, due to the presence of allergens in the air or as part of the symptoms of hay fever. In this case, the typical symptom is mainly tearing and burning of the eyes and redness of the conjunctiva. Topical anti-allergy ointments or drops work best for allergies, as do conventional tablets. Various degenerations or deformations of the conjunctiva also occur as a result of pathological causes, for example, if the conjunctiva becomes adherent to other tissue close to the eye.

Some ulcers are also problematic, as they can affect the conjunctiva directly as part of the inflammation, or they can get there through passage from the eyelid. However, flat ulcers and defects are more often formed as complications of both allergic and infectious inflammations of the cornea or directly of the conjunctiva. Swelling can also occur on the conjunctiva, for example in conjunction with swelling of the eyelashes or eyelids. Sometimes the eyes are also sealed by the production of secretion in the case of swellings or ulcers.

In addition to ulcers, trachomas or small vesicles can form on the conjunctiva from both inflammatory and non-infectious causes. In addition, vascular disorders are a major problem, especially if there is bulging of the blood vessels, which impairs the blood supply to the conjunctiva itself, and this can develop into problems with secretion and drying of the conjunctiva. Drying out also occurs in some types of inflammation, when the parts of the epithelium that are responsible for the secretion of the conjunctiva and the eye are affected.

Tumours and other diseases of the conjunctiva

Other diseases affecting the conjunctiva include, for example, pterygium, pseudopterygium, various conjunctival scars such as symblepharon, conjunctival haemorrhage, subconjunctival haemorrhage, but also, for example, various tumours. Non-malignant tumours include, for example, haemangiomas, but much more common are malignant tumours that can affect the conjunctiva directly, such as conjunctival melanoma, or invade it from the eyelid, for example, which is the example of eyelid carcinoma.

These tumours need to be surgically removed, but still have a high recurrence rate. Pterygium and pseudopterygium are also a problem. While pterygium is a hyperplasia of the conjunctival fibrovascular tissue, pseudopterygium is a post-traumatic adhesion arising between the vitreous, cornea and conjunctiva that is scar-like in nature. Pterygium also grows over the cornea of the eye and is an enlarged duplication of the conjunctiva.

It is shaped like a grey triangular head that grows towards the centre of the cornea and it is necessary to remove this head surgically. Pseudopterygium scarring occurs when the eye is damaged mechanically, chemically or by excessive heat, and this formation also needs to be removed surgically to prevent further damage to the conjunctival tissue.