- solen.sk - ANEMIA - DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

- solen.sk - Anemia - diagnosis and differential diagnosis

- solen.sk - Vascular aspects of haemoglobinopathy

- mayoclinic.org - Vitamin deficiency anemia

- mayoclinic.org - Aplastic anemia

- ncbi.nlm.nih.gov - Thalassemia

- healthline.com - Best Diet Plan for Anemia

Anemia, anemia: what is it, what causes and symptoms? + Types

Anemia of the blood is otherwise known as anemia. It is a blood disorder in which there is a decrease in hemoglobin and thus a decrease in the number of red blood cells.

Most common symptoms

- Malaise

- Feeling of heavy legs

- Chest pain

- Headache

- Spirituality

- Deformed nails

- Tinnitus

- Bleeding

- Brittle nails - onychoschizia

- Brittle hair

- Indigestion

- Nausea

- Tingling

- Malnutrition

- Memory disorders

- Cold extremities

- Pressure on the chest

- Head spinning

- Tremor

- Tremors

- Fatigue

- Yellow whites of the eyes

- Yellowish skin

- Accelerated heart rate

- Liver enlargement

Characteristics

Anemia - anemia, anemic syndrome. What is blood deficiency and why does it arise, how does it manifest itself?

Human blood contains three types of blood cells, which are formed in the bone marrow called hematopoiesis.

White blood cells are used to fight infections, platelets stop bleeding and red blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body and carbon dioxide from the body back to the lungs.

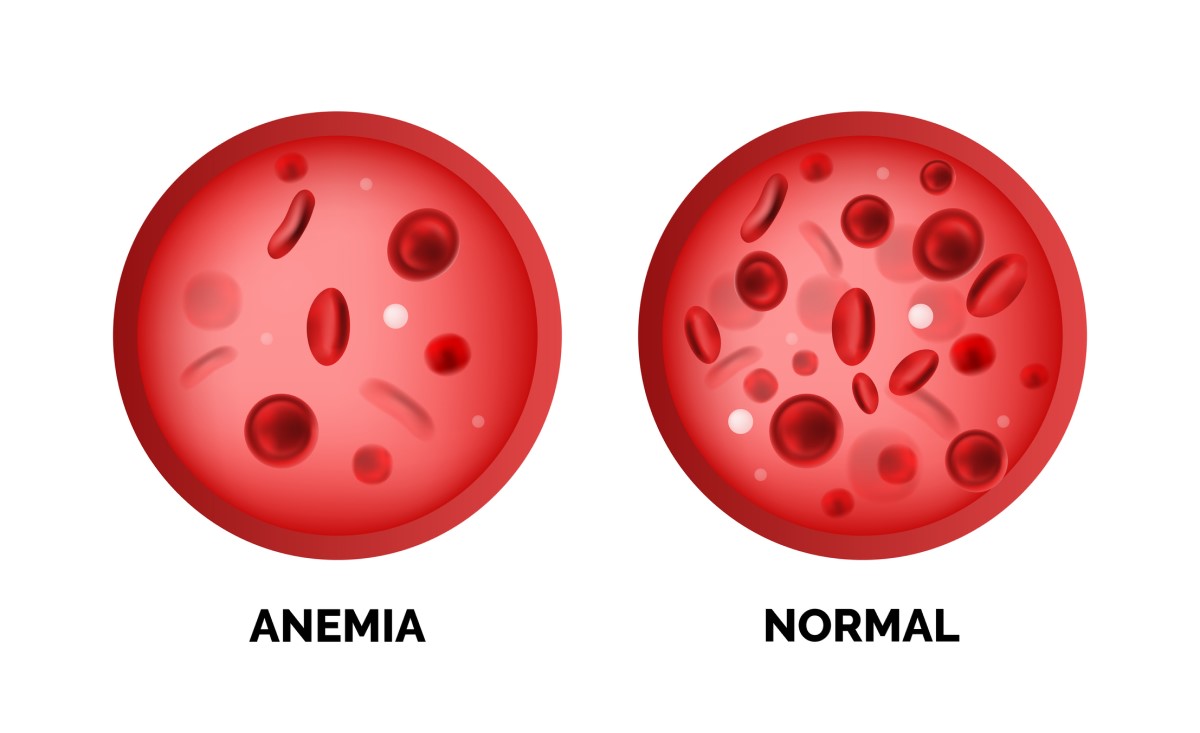

Anemia, or anemia, is a pathological condition characterized by a decrease in the number of red blood cells (called erythrocytes) and hemoglobin below the normal physiological value.

Anemia is clinically presented as an anemic syndrome. The leading symptoms are pallor of the skin and mucous membranes, fatigue and general weakness.

Anaemia is defined as low haemoglobin, red blood cell and haematocrit levels.

It is a condition in which there is a lack of sufficient healthy red blood cells, which ensure the transfer of oxygen to all organs and tissues of the human body. The clinical manifestation of anaemia is the so-called anaemic syndrome, the leading symptom of which is fatigue and weakness.

There are several types of anaemia. Each type has its own cause.

Anaemia can be acute, temporary or chronic. It can deepen to several degrees, from mild to severe anaemia, which requires treatment with blood transfusions.

The most important sign confirming anaemia is a low haemoglobin level.

Haemoglobin (Hg) is a blood pigment that gives blood its red colour. It is found in red blood cells (erythrocytes). Haemoglobin is an iron-rich haemoprotein and makes up 35% of the erythrocyte content.

Haemoglobin is able to bind oxygen, which we breathe, and carbon dioxide, which we subsequently expel by breathing, in the lungs.

This ensures the supply of oxygen to all cells and the removal of excess carbon dioxide, which is produced as waste during biochemical processes in the tissues.

The haemoglobin content of erythrocytes differs between men and women.

Haemoglobin levels below 135 g/l in men and below 120 g/l in women are considered pathological, i.e. anaemic.

Most blood cells, including red blood cells, are regularly formed in the bone marrow - the spongy bone tissue found in the cavities of large bones.

Anemias can be classified on the basis of the pathological appearance of the erythrocyte (i.e., morphologically) or on the basis of the mechanism of anemia (by etiology).

The morphological classification includes normocytic anaemia, in which there are few erythrocytes in the blood but normal in shape. The second type is macrocytic anaemia, i.e. anaemia with very large erythrocytes. The third type is microcytic anaemia, in which there are too few erythrocytes in the blood.

A special type of anaemia is sickle cell anaemia, in which the erythrocytes are crescent-shaped.

The characteristic pathological shape of the erythrocyte can be used to judge the mechanism by which the anaemia has occurred.

Normocytic anemias include:

- Acute posthemorrhagic anemia

- Hemolytic anemia

- Anemia in chronic diseases

- Anemia in bone marrow infiltration

- Hypoplastic anemias

In these types of anemias, normal amount of hemoglobin is found in the erythrocyte. Therefore, they are called normocytic and normochromic anemias.

Macrocytic anemias include:

- Megaloblastic anemias

- Anemia with increased erythropoiesis, i.e., rapid synthesis of blood cells in the bone marrow during acute losses (hemorrhage, blood cell breakdown) when the body tries to rapidly replace the blood deficit.

The erythrocytes in this type of anaemia contain too much haemoglobin and are therefore called hyperchromic.

Microcytic anemias include:

- Sideropenic anemia

- Hemoglobinopathy (thalassemia)

- Anemia in chronic blood loss

- Sideroblastic anemia

The haemoglobin and iron content of the erythrocyte in microcytic anaemias is reduced, hence they are called microchromic anaemias.

Causes

Anaemia can be present at birth (called congenital anaemia) or develop at any time during life (called acquired anaemia).

A situation where there are not enough red blood cells in the blood can occur because:

- the body does not make enough red blood cells

- the loss of red blood cells is faster than the replacement mechanisms, e.g. during bleeding

- the body destroys red blood cells

Types of anaemia according to the cause

1. Iron deficiency anaemia

This type of anemia is called sideropenic anemia and is one of the most commonly occurring anemias. Its cause is due to iron deficiency in the body.

The bone marrow, in which red blood cells are produced, needs iron to make hemoglobin. Without the necessary amount of iron, the necessary amount of hemoglobin for red blood cells will not be made.

Causes of iron deficiency:

1. Blood loss - There is a large amount of iron in the blood contained in the red blood cells. If there is blood loss (bleeding), iron is also lost from the body. For example, women who have excessive menstrual bleeding are at risk for iron deficiency anemia.

Subtle blood loss occurs in slow, chronic (so-called hidden) bleeding - for example, from a stomach or duodenal ulcer, hiatal hernia, colon polyp or colorectal cancer.

Such bleeding is known as occult bleeding and can be investigated simply from a stool sample. It is a relatively common cause of chronic iron deficiency anaemia.

Gastrointestinal bleeding from the gastric mucosa can also be caused by the regular use of certain over-the-counter antiphlogistic and painkillers.

2. Dietary iron deficiency - the main source of iron for the human body is food. Examples of iron-rich raw materials are meat, eggs and leafy vegetables in the first place.

The growing body has the greatest requirement for iron supply. Therefore, a balanced diet is important especially during infancy and childhood.

3. Inability to absorb iron - Iron is absorbed from food into the blood in the small intestine. Intestinal diseases such as celiac disease or inflammatory diseases negatively affect the ability of the intestine to properly absorb all nutrients from food.

Patients who have had surgery to remove part of their small intestine may suffer from anaemia slightly more often.

4. Pregnancy - Pregnancy is a period when the body has increased requirements for all important nutrients and trace elements. This includes iron.

Pregnant women should take dietary supplements fortified with iron. Otherwise, they may develop anemia, which is dangerous for the developing fetus. Women during this period have an increased volume of their own blood, and they also produce hemoglobin for the growing fetus.

Prevention of iron deficiency in the body

The most effective way to avoid iron deficiency in the body is by choosing quality foods high in this element.

Iron-rich foods:

- Red meat, pork and poultry

- Seafood

- Legumes such as beans and peas

- Dark green leafy vegetables such as spinach

- Dried fruits such as raisins and apricots

- Cereals

The body absorbs iron best from meat as it does from plant sources. Vegetarians should include legumes, cereal products and supplements in tablet form in addition to a rich plant-based diet.

Vitamin C contributes significantly to the proper absorption of iron from the diet, so it is important to consume foods fortified with this vitamin.

Foods containing vitamin C to increase iron absorption:

- Citrus fruits and citrus juices such as orange, grapefruit, tangerines

- broccoli

- kiwi, strawberries, melon

- leafy vegetables

- peppers and tomatoes

Prevention of iron deficiency anaemia in infants

A rapidly growing body requires a high intake of iron in the diet. The baby receives iron for the first year of life from breast milk or through artificial iron-fortified formula.

Cow's milk is not a good source of iron. It is not even recommended for infants because of the inappropriate ratio of protein, casein and whey. After 6 months, the infant is fed meat purees at least twice a day to increase iron intake.

2. Vitamin deficiency anaemia

In addition to iron, the body needs folate and vitamin B12 to produce sufficient healthy red blood cells. If the diet does not contain enough of these vitamins, red blood cell production may be slowed or restricted.

Some people consume enough vitamin B12, but their body is unable to absorb the vitamin properly. This condition leads to vitamin B12 deficiency anemia, which is also known as pernicious anemia.

Vitamin B12 deficiency can be caused by:

1. Diet - Vitamin B12 is mainly found in meat, eggs, and milk. For this reason, vegans and vegetarians who do not eat these types of foods should take supplements containing vitamin B12. In addition to animal products, nutritional yeast and its products are also good sources of B vitamins.

2. Stomach surgery - After surgery, when part of the stomach or small intestine is removed, the body's ability to absorb B12 is limited as a result. The body lacks the so-called intrinsic factor or intrinsic factor, which is essential for proper absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

Intestinal diseases - Crohn's disease and celiac disease make it difficult to absorb vitamin B12. Parasites in the intestines, such as tapeworms, which can be contracted by eating raw contaminated fish, also limit vitamin B12 absorption.

Folic acid deficiency:

Folic acid or folate, also known as vitamin B9, is a nutrient found mainly in dark green leafy vegetables and animal liver.

Difficulties with folate absorption occur with these conditions:

- Intestinal diseases such as celiac disease

- Surgical removal or bypass of a large part of the intestine

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Certain medications, such as anti-seizure medications

- Pregnant women and women who are breastfeeding have increased requirements for folic acid intake

- People with kidney disease and on dialysis

Foods rich in vitamin B12:

- Beef, liver, chicken and fish

- Eggs

- Milk, cheese and yoghurt

The recommended daily allowance of vitamin B12 for a healthy person is 2.4 micrograms.

For the chronic diseases mentioned above, a multiple of the recommended daily dose is required.

In addition to macrocytic anaemia, vitamin B12 deficiency can manifest itself in other symptoms. Nervous system disorders such as persistent tingling in the hands and feet or balance problems are common. Mental changes or forgetfulness may also occur.

Pernicious anaemia, which occurs when vitamin B12 is not absorbed sufficiently, increases the risk of stomach or bowel cancer.

Folic acid deficiency, especially in the period before conception and during pregnancy, can cause birth defects in the foetus, especially neural tube defects, which manifest as birth defects of the brain and spinal cord, such as anencephaly, myelomeningocele or meningocele.

Some association with folic acid deficiency has also been demonstrated in the occurrence of congenital heart disease or Down syndrome.

The use of folic acid supplements is an effective way to prevent congenital birth defects, starting 3 months before the planned pregnancy, throughout pregnancy and for at least 6 weeks after delivery or throughout lactation and breastfeeding.

The recommended dose is 400 micrograms per day. If there is a family history of neural tube defect, a 10-fold higher dose of folic acid (4-5 milligrams per day) is recommended to prevent recurrence.

Foods high in folate:

- Broccoli, spinach, asparagus and beans

- oranges, lemons, bananas, strawberries and melons

- liver, kidneys

- yeast, mushrooms

- nuts, peanuts

3. Anemia in chronic diseases

Some severe chronic diseases adversely affect the process of red blood cell production and may cause their early demise or condition blood loss.

These include cancer, HIV/AIDS, inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, kidney disease, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, among others.

4. Aplastic anaemia

This type of anemia is one of the rarer causes of anemia. However, it is a life-threatening anemia.

Stem cells found in the bone marrow produce three types of blood cells - red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

In aplastic anaemia, these stem cells are damaged, causing the bone marrow to become 'dysfunctional'. The bone marrow becomes empty or aplastic or contains few blood cells (is hypoplastic).

The most common cause of aplastic anaemia is the immune system's own fight against the stem cells in the bone marrow - an autoimmune reaction.

Other risk factors that can cause aplastic anemia:

- Cancer treatment - chemotherapy and radiation therapy - in addition to cancer cells, healthy cells, including stem cells in the bone marrow, can be damaged.

- Toxic substances and chemicals - exposure to pesticides and insecticides or additives that are mixed into gasoline are associated with the development of aplastic anemia

- Use of certain drugs, for example to treat rheumatoid arthritis, and certain antibiotics

- The presence of other autoimmune diseases is a risk factor for the development of autoimmune-related aplastic anaemia

- Viral infections, especially viruses causing hepatitis, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19 and HIV

- Pregnancy

- Unknown factors - sometimes doctors cannot determine the exact cause of aplastic anaemia, when it is called idiopathic aplastic anaemia

5. Anemia in bone marrow diseases

Diseases such as leukaemia or myelofibrosis cause anaemia, which can be life-threatening.

6. Haemolytic anaemia

This type of anemia occurs in situations where red blood cells are destroyed faster than the bone marrow can replace them by producing new blood cells.

Increased destruction of red blood cells is caused by certain inherited diseases, such as congenital disorders of the erythrocyte membrane, or by a defect in the enzymes needed for proper erythrocyte function.

Such anemia resulting from a defective red blood cell is called corpuscular hemolytic anemia. However, hemolytic anemia can also occur when the problem is outside the erythrocyte. Then it is called extracorpuscular hemolytic anemia.

Examples are autoimmune reactions against red blood cells, lymphoproliferative cancers, monoclonal gammopathy or the use of certain drugs, such as methyldopa, a centrally acting antihypertensive.

Hereditary anaemias

1. Sickle cell anaemia

This is an inherited form of haemolytic anaemia. It is caused by a mutation in the gene responsible for the production of the iron-rich protein in red blood cells, haemoglobin.

The role of haemoglobin is to carry oxygen from the lungs to the body. The mutated gene produces haemoglobin with a faulty structure. Therefore, the red blood cells formed are not disc-shaped biconcave but elongate into a sickle shape.

Erythrocytes deformed in this way are formed mainly during deoxygenation, i.e. after oxygen has been transferred to the tissues.

In the reversible form of the disease, the erythrocytes can change back to their normal shape during oxygenation. In the irreversible form, on the other hand, the erythrocytes remain in a sickle shape permanently, unaffected by oxygen.

Sickle-shaped red blood cells have different rheological properties, are stickier and tend to clog blood vessels. The spleen detects and destroys such defective erythrocytes - haemolysis occurs and anaemia worsens.

2. Thalassemia

Thalassaemia is a hereditary disease classified as a haemoglobinopathy, similar to sickle cell anaemia. It is therefore the formation of defective haemoglobin - the red blood pigment.

Haemoglobin molecules are composed of two chains called alpha and beta chains. In thalassaemia, the production of either alpha or beta chain is reduced. According to the type of broken chain, alpha-thalassaemia or beta-thalassaemia is distinguished.

When one of the chains is disrupted, there is increased production of the other hemoglobin chain. The result is an erythrocyte that contains non-functional hemoglobin and many residual other chains that are stored and useless in the erythrocyte.

Such a cell is more rapidly subject to destruction (hemolysis), which causes anemia and hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen due to the accumulation of destroyed erythrocytes).

Symptoms

Symptoms of anemia vary depending on the cause of the degree and severity of anemia.

All symptoms can range from mild to severe and life-threatening.

In general, the following are considered the most common symptoms of anemia:

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Pale or yellowish skin

- Irregular heartbeat - arrhythmia

- Difficulty breathing and shortness of breath

- Dizziness or light-headedness

- Chest pain

- Cold hands and feet

- Headache

- Brittle nails

- Unusual taste for non-nutritive substances such as ice, dirt or starch

- Indigestion, especially in infants and children with iron deficiency anaemia

- Frequent, recurrent or prolonged infectious diseases

- Unexplained and easily bruising

- Frequent nosebleeds and bleeding gums

- Unstoppable bleeding from wounds, e.g. cuts

- Change in mental state

- Forgetfulness

- Tinnitus

- Tingling in the hands and feet

Diagnostics

An important part of the diagnosis is a medical history. The doctor will ask about your health, increased fatigue, neurological symptoms or signs of increased bleeding, such as prolonged bleeding during menstruation or blood in stools or vomit.

The family history will be of interest for the presence of congenital types of anaemia or hereditary bleeding disorders.

In a personal history, an indication of frequent infectious diseases, cartilage or kidney problems is important. Medications you take or exposure to chemicals or excessive alcohol consumption are also essential.

Of the laboratory tests, a complete blood count is essential. A blood count is actually a count of the number of blood cells from a sample of venous blood taken. The level of red blood cells (hematocrit) and the hemoglobin level in the blood informs about anemia.

The threshold for anaemia is determined by the haemoglobin level and is dependent on age and sex (table)

| in children aged 1 to 6 years | 110 g/l |

| in 6-14 year olds | 120 g/l |

| in males | 135 g/l |

| in non-pregnant women | 120 g/l |

| in pregnant women | 110 g/l |

Severity of anaemia by haemoglobin level:

- mild anaemia (if haemoglobin does not fall below 100 g/l)

- moderate anaemia (haemoglobin 80-100 g/l)

- severe anaemia (haemoglobin below 80 g/l)

These values may be lower even in healthy people, for example those who engage in intense physical activity, in pregnancy or in the elderly. Smoking and living at high altitude, on the other hand, increase the erythrocyte count.

Another parameter that we can examine in the blood count is the size of the red blood cells. In addition to size, the unusual shape of the red blood cells and their similarity are also assessed, e.g. anisocytosis (uneven size of the erythrocytes) or poikilocytosis (uneven shape of the erythrocytes)

In the blood count, however, we do not only look at the red component of the blood, but also at other blood cells and particles. The number of leukocytes, neutrophils and the number of platelets are important.

An essential laboratory test in the diagnosis of any anaemia is sedimentation and chemical examination of the urine or stool analysis.

Other diagnostic tests depending on the type of anemia:

- Blood iron metabolism tests (determination of serum iron and serum transferrin or soluble transferrin receptor concentrations).

- bone marrow examination

- immunohematological tests (blood group, antiglobulin tests)

- examination of immunoglobulin levels

- erythrocyte enzyme values

- markers of hepatitis and other viral diseases

- oncomarkers

- rheumatological examination

- endocrinological examination

- gastroenterological examination

Course

The course of anemia depends on the provoking cause.

Some anaemias are hereditary and are present from birth. Acquired anaemias, such as anaemias in chronic diseases or pernicious anaemias, are characterised by a slow worsening of the red blood cell deficiency and therefore a more gradual deterioration of the clinical condition.

The acute course of anaemias is characterised by massive and rapid blood loss, e.g. due to trauma.

Tento článok vznikol vďaka podpore spoločnosti Hemp Point CBD Slovensko.

How it is treated: Anemia - anemia

Treatment of anemia: How to treat and what drugs are used + vitamins

Show moreAnemia is treated by

Other names

Interesting resources

Related

- Iron,